What’s Changed in Pediatric Melanoma Treatment

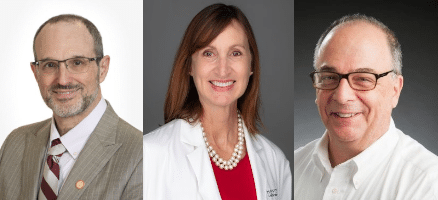

Guest blog post by Vernon K. Sondak, MD (Department of Cutaneous Oncology, Moffitt Cancer Center), with Jane L. Messina, MD (Departments of Cutaneous Oncology and Anatomic Pathology, Moffitt Cancer Center) and Alberto S. Pappo, MD (Department of Oncology, St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital):

“What’s changed in pediatric melanoma?” is a question Dr. Messina and I posed in a recent editorial[i] written about a journal article[ii] authored by Dr. Pappo and his team (all three of us have been members of the Melanoma Research Foundation’s Pediatric Melanoma Steering Committee for the past several years). The answer we gave to that question was “pretty much everything.” In part 1 of our “What’s New in Pediatric Melanoma?” blog, which you can find here, we talked about what has changed in the pathologic diagnosis of pediatric melanoma and atypical Spitz tumors. In today’s blog we will talk about what has changed in the surgical and medical treatments of melanoma in children and adolescents. Of course it’s important to remember that an awful lot has changed in the treatment of melanoma in adults over the past 10 years,[iii] with new surgical approaches and new drugs combining to decrease the death rate from adult melanoma nearly 30% in the past 5 years with less long-term surgical side effects than ever before. Almost all of these improvements have influenced our treatment of melanoma in children under 18 years of age, even though relatively few children have been enrolled in clinical trials.

Let’s start with surgery. For just about any type of pediatric melanocytic lesion, whether fully malignant or atypical, the mainstay of surgery continues to be complete removal of the skin lesion, with sentinel node biopsy when necessary. It goes without saying that you can’t get the right surgery if you don’t get the right diagnosis, so the advances we talked about in Part 1 of this blog will help ensure that pediatric patients get the right diagnosis and operation with the hope of decreasing the number of patients who are offered a sentinel node biopsy simply because we are not sure about the malignant nature of the tumor – as often happens with the diagnosis of “atypical Spitz tumor.” And thanks to those diagnostic advances, we believe that children with lesions that have been evaluated by molecular analysis and lack any features of melanoma (such as a positive FISH result or TERT promoter mutation) generally no longer need sentinel node biopsy. For pediatric patients with proven melanoma, sentinel node biopsy remains an important part of their surgical care. Clinical trials are underway in adults to try to predict which melanomas will actually have a positive sentinel node, in an effort to identify which patients may not require sentinel node biopsy. At present, none of these trials are enrolling pediatric patients, and we do not believe that any commercially available prognostic tests are able to identify children with melanoma who do or do not require sentinel node biopsy except for the standard pathology features such as Breslow’s thickness and ulceration.

Once a sentinel node biopsy has been done and analyzed by the pathologist, however, a lot has changed. Completion lymph node dissections, which are second surgeries to remove all the remaining lymph nodes in a nodal region where the sentinel node showed melanoma, are becoming a thing of the past for both adults and children. Instead, sentinel node-positive melanoma patients routinely have “active surveillance” of their remaining lymph nodes, with physical examination and scans – often including ultrasounds of the lymph nodes, which doesn’t involve x-ray exposure – and only have node dissection surgery if the melanoma reoccurs in the lymph node basin. While we are doing less surgery for sentinel node-positive cases, we are doing more drug treatment – referred to as adjuvant therapy – to try to decrease the chance for recurrence, especially when we see any high-risk features in the primary tumor and/or the nodal metastasis. Both immunotherapy and BRAF-targeted therapy (for melanomas with a BRAF mutation) are FDA approved for adjuvant therapy of adult melanoma, and both are used for pediatric melanoma patients as well. More than half of all pediatric melanomas have a BRAF mutation, so BRAF-targeted therapy is available as adjuvant therapy for many sentinel node-positive children. Currently, we prefer to use BRAF-targeted adjuvant therapy for our children with node-positive melanoma, because there seems to be a lower risk of long-term side effects compared to immunotherapy, even though these kinds of side effects are rare with either type of treatment. In adults, there is even a move towards using adjuvant therapy in very high-risk cases of sentinel node-negative melanoma, but it likely will be a long time before we have enough information about that to routinely recommend it for children.

In more advanced cases of melanoma, whether stage III melanoma with enlarged lymph nodes or stage IV melanoma that has spread beyond the lymph nodes to other organs, we have more choices than ever in terms of treatment. Surgery, immune therapy and BRAF-targeted therapy are all options for these patients, and increasingly the question is not “what treatment should my child have?” it’s “what treatment should my child have first?” That’s because the sequence of treatment has been evolving as fast or faster than the treatment options we have. For example, we are using drug therapy to shrink the size of enlarged lymph nodes before surgery to make surgery easier and learn about the responsiveness of the tumor to treatment, an approach we call neoadjuvant therapy. Not yet widely used in children, we have had good success with this approach in teenagers with enlarged nodes at Moffitt. There are also times when surgery can help out with cases of stage IV melanoma. One thing we cannot stress enough is that the availability of many different treatment options makes it even more important that specialists with experience in treating childhood melanoma are consulted whenever a child has an advanced case of melanoma.

To summarize, there really have been new developments in just about every aspect of melanoma management – for children just as well as adults. But getting your child seen by a specialist in pediatric melanoma (which might be at an ‘adult’ cancer center like Moffitt or at a children’s hospital like St. Jude’s) is just as important as ever.

Life-saving advances in pediatric melanoma research are made possible by supporters like you. In honor of Pediatric Melanoma Awareness Month, please consider a tax-deductible donation today:

[i]. Sondak VK, Messina JL. What’s new in pediatric melanoma and spitz tumors? Pretty much everything. Cancer 2021; 127:3720-3723.

[ii]. Pappo AS, McPherson V, Pan H, et al. A prospective comprehensive registry that integrates molecular analysis of pediatric melanocytic lesions. Cancer 2021; 127: 3825-3831.

[iii]. Curti BD, Faries MB. Recent advances in the treatment of melanoma. N Engl J Med 2021;384:2229-2240.

Disclosure Information:

Dr. Sondak reports personal consulting fees from Bristol Myers Squibb, Eisai, Merck, Novartis, Regeneron and Replimune. Dr. Messina and Dr. Pappo report nothing to disclose.